Koka vs the World

I love statically typed functional programming. Building up programs in statically typed functional style feels like a conversation with the compiler about what is possible.

Python fanatics tell me over and over that you can’t prototype that way. Unfortunately, heartbreakingly, sometimes they’re right.

Prototyping

Sometimes it is much easier to get to a useful product if you accept that you don’t understand how it works in an edge case. I wanted a compiler that could say “I can work with this, but you should clean it up later”. I didn’t found one.

Postgres

Sometimes you need to interact with complicated, outside resources like databases, and purity feels like a fools errand. I wanted a compiler that would let me compose with impunity, but still remember that somewhere in the program I need to give it a database. I didn’t found one.

Performance

This has become somewhat less important now that the frame of reference for a lot of people is javascript and python rather than C, but functional languages can perform quite badly and use a lot of memory because they want everything to be immutable. I wanted a compiler that could take nice functional code and rewrite it based on the context to be performant and imperative, but somewhere I didn’t have to see it. I didn’t find one.

Preferences

Sometimes you have someone on your team who has the same love of mutable state that I have of static types and function composition. I wanted a compiler that could let them have their fun, but create clean, tight barriers around mutations so that I could see from the type whether or not I had to deal with that nonsense. I didn’t find one.

I did not expect these problems to have the same solution. I thought these were unrelated flaws of the languages I loved, and that the only solution was to work in multiparadigm languages and be very very careful because I could never quite trust the types. I figured that if the problem were solvable, someone would have solved it in the last 47 years of research.

Then a friend showed me Koka.

Effect Types for Prototyping

The first thing I saw reading about Koka was that it had exceptions, and I almost gave up there. Exceptions are the biggest footgun that I have to worry about on a daily basis. Seeing them in a nice pure language I felt cheated and lied to. But in Koka, something is different when you throw an exception; it is captured in the type.

fun first(l: list<a>) {

match (l) {

Cons(head, _) -> head

}

}

This code takes a list and gives back its first element. There are cleaner ways to do this, but for illustration I wanted to write it out fully.

In most functional languages, this wouldn’t compile. “That pattern matching isn’t complete”, they would say. “What if you got an empty list?” they would say. So programmers, not able to explain to the compiler that they are absolutely certain that won’t happen, switch away from such languages to something a little more practical (typescript) and just let the code throw.

Everybody lives happily ever after, until this prototyping code is embedded in the core of a Very Important Model being used in production, and it actually does get an empty list because the code has been rewritten half a dozen times since the programmer was absolutely certain that couldn’t happen. But in Koka, unlike in typescript, the return type of this function remembers that there can be an exception. The return type here is inferred as exn a rather than just a. Any function calling this also gets that exn effect added to its type, until the programmer goes back and deals with that effect and removes it everywhere or catches it with an effect handler.

fun dumb(): either<string, nirvana> {

with control raise(message) {"Why did you think that would work?".Left}}

first(Nil).Right

}Now anything calling dumb can be certain that the exception was handled, and doesn’t need to worry about it anymore. This gives us a clean way to iteratively integrate prototype code into a production codebase, by looking at the type and controlling for unknowns or rewriting to rule them out.

Effect Types for Postgres

I was sold. You could write exceptional code and prototype away, and clean up after yourself later. I figured that was it, that was the clever trick for this language, but effect types are so much better than that. Effects aren’t limited to those defined in the language, you can make up your own in user land. This means that I can write an effect like this;

effect val postgres : dbConnection

fun app() : postgres {

.... // arbitrary use of postgres at any depth as a value internally

}

fun main() {

with val postgres = realConnection

app()

}

fun test() {

with val postgres = testMock

app()

}This is dependency injection, but without any of the horrible nonsense of passing dependencies down all the way through the application or currying everywhere to create versions of services with the dependency in the closure. Any function can say “I need access to the database” by declaring the effect, and Koka handles the rest. This magic is actually the same semantic that Koka used to define exceptions, restricted to the case where the result of the effect was always a single value. And even better, while real database connections probably have all sorts of gross side effects, this injection can be polymorphic over the effect to let us be sure that our code in the test case can stay pure and deterministic.

Effect Types (and Trailing Lambdas) for Preferences

Alright, that’s it then. Effect types solve the prototyping problem, and give a beautiful new pattern for dependency injection. What more can we ask for?

One of the biggest barriers that functional languages face is just about what people already know. Programmers want to write loops because they are used to loops, and it doesn’t matter if there is an equivalent functional program; if they aren’t used to it it will be harder to debug and not worth their time. But Koka has while loops. And they are functions, defined in user land.

fun while( predicate : () -> <div|e> bool, action : () -> <div|e> () ) : <div|e> ()

{

if (predicate()) {

action()

while(predicate, action)

}

}

while {condition == true} {

println("I'm secretly functional!")

}while here is just a function, with Koka providing a bunch of syntactic sugar to make the way you call it more familiar to those comfortable in imperative languages. The fact that it’s still a function means that all of the composable semantics that we get out of effect types and function composition still apply to code using loops of this form, even though the code looks dirty and imperative. Even the infinite loop here is captured by the type system. Koka infers that anything using this function has the div effect, meaning it might run forever without producing a value. This is the same effect it would infer for a recursive function, because while is a recursive function.

This effort to preserve the intuition of developers coming from imperative languages extends way beyond fake looping constructs. It should say something that while I couldn’t find a syntax highlighter for koka to use on these code blocks, the javascript syntax highlighting looks pretty much fine. The language as a whole is designed to feel familiar to people used to C family syntax, but give superpowers that nothing in that family has.

No Compromises

Usually, having discovered something beautiful and powerful that checks so many boxes, the cost is performance. Asking computers to do something so completely unrelated to their memory model is expensive, and so such languages usually come with bloated, slow runtimes that do the translation at the last possible minute. Sometimes, very clever compilers do things like tail call optimization to take common functional patterns and statically transform them into loops, but that can only go so far. While the nice tricks Koka is playing to give us mutable variables look like they do in-place updates, they still desugar to slow, piggy functions.

Just kidding. They become stupid fast in-place updates with no need for a garbage collector.

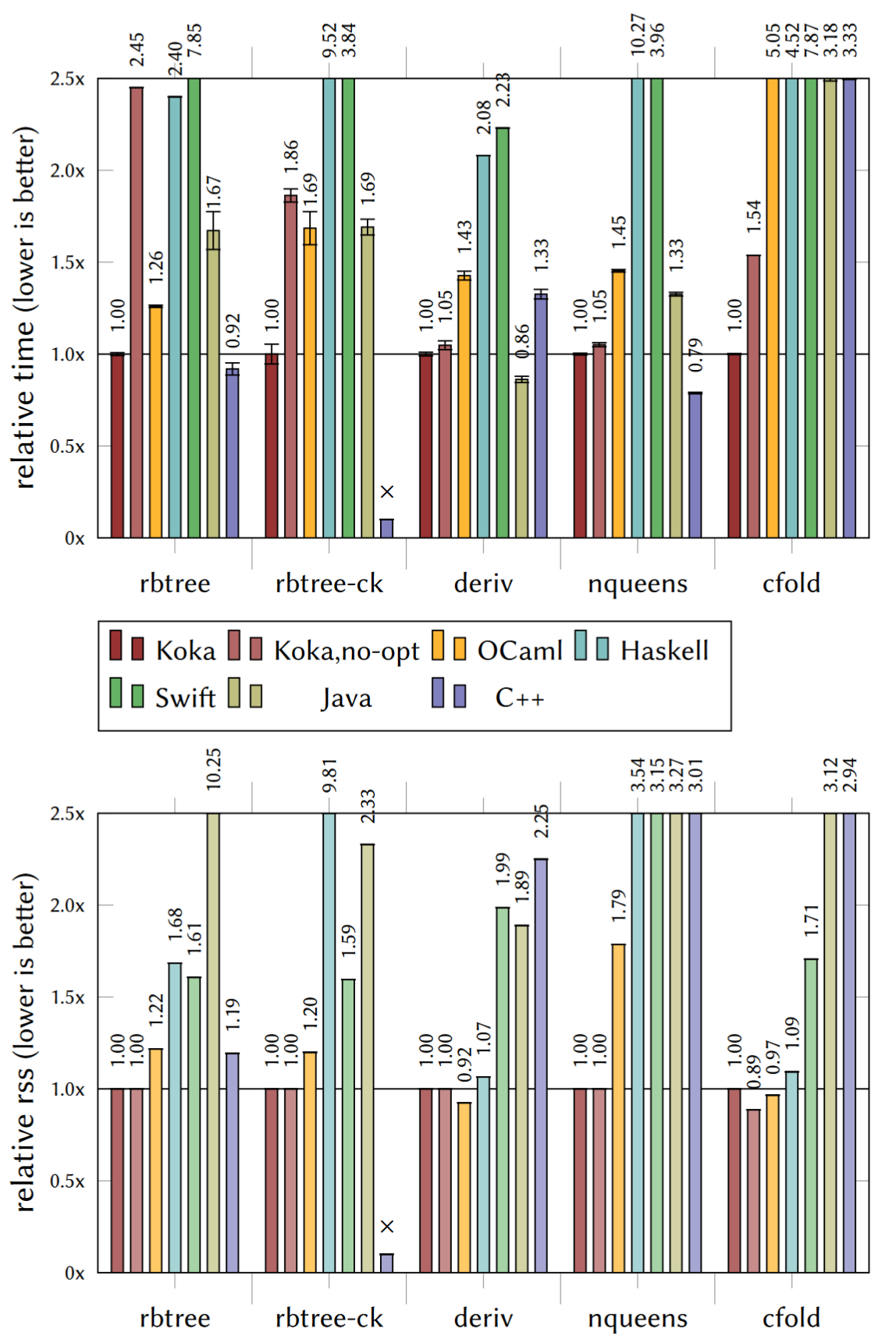

Koka does transform those mutable variables into a state effect to make sure to have all of the wonderful functional semantics that help us keep code composable, but it also uses the Perceus compiler to transform that state effect into in-place updates wherever possible. Reuse analysis is even more powerful, taking clean functional expressions like list maps or tree traversals and transforming them into in-place mutations whenever possible, gracefully degrading back to shared memory persistent representations when not. The Koka book explains this much better than I can, but it is worth glancing at the benchmarks they’ve done so far.

This unfinished research language can outperform C++. Benchmarks should always be taken with an ocean of salt, and these problems certainly weren’t chosen at random, but the firm foundation of Perceus gives me hope that these results are real and will be borne out in practice.

It is early days for Koka. It isn’t ready for production, and new languages usually aren’t adopted, but there is so much in Koka that is fundamentally better than existing languages that I would be heartbroken if these things didn’t catch on. Maybe it is a stepping stone, and something else will productionalize these ideas, but it is hard to imagine changing very much. Koka improves on the state of the art in so many places that it feels to me like making it productional is the path forward, rather than adopting these ideas into other languages.